Knowledge Transfer 2.0 – Making biodiversity research effective for biodiversity conservation

The conservation and sustainable management of forests is increasingly regarded as an effective measure for forest biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation by science, policy makers and society. Thus, the importance of the multifunctionality of forests is currently rising, as are potential trade-offs among demanded ecosystem functions. There are, for example, synergies between the stability of a stand and its structural diversity, and conflicts between species that require a stable and moist forest microclimate of dense forest interiors and species that need the warm and open conditions of larger canopy gaps or an open canopy.

One central aim of the Biodiversity Exploratories (BE) is the understanding of relationships among biodiversity, ecosystem functions (including both ecosystem processes and services) and forest management, and the consequences of different forms of management on biodiversity and associated processes and functions on different spatial scales. This understanding may help to identify synergies or conflicts between different ecosystem functions (e.g., the habitat function for specific species) and management goals (e.g., timber production), as well as provide a supporting system for complex decisions in forest and nature conservation practice.

In the Knowledge Transfer Project of the Biodiversity Exploratories (BE) we want to foster the bilateral transfer of results, knowledge, and experiences between the BE and forestry and nature conservation practice, and thereby increase the effectiveness of biodiversity research for biodiversity conservation. In particular, we would like to:

- Regularly communicate the practice-relevant research results of the BE

- Improve and support the direct communication between scientists and practitioners of nature conservation, forestry, and hunting

- To integrate the knowledge, the experiences, and the open questions of practitioners into the research of the BE

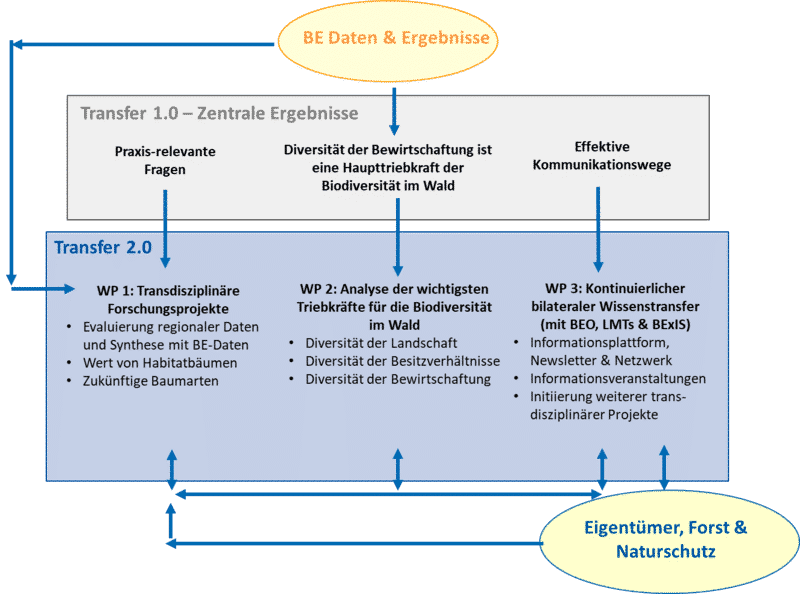

Based on results of the previous project phase of the Biodiversitsy Exploratories (BE; see results section) the current Knowledge Transfer 2.0 project comprises three work packages (see Fig. 1):

- Transdisciplinary research projects

- Analysing the most important drivers of biodiversity in forests

- Regular bilateral knowledge transfer

WP 1 – Transdisciplinary research projects

In the previous phase, we conducted a survey among representatives of forestry and nature conservation practice, subsequent interviews and joint workshops to define research topics and questions that are currently highly relevant and that should be integrated into research projects of the BE in the future. In WP1 we will work together with the application partners of the three regions on three out of the 49 defined questions:

1.1 Comparison of BE data with data collected within the protected areas of the BE regions to identify general patterns or limitations of data representativeness of the BE

1.2 Evaluation of the effect of old and habitat trees and their conservation in forests for biodiversity and revenues

1.3 Identification of tree species within the BE research plots that may show a high vitality under the expected climate change and that are associated with high biodiversity

WP 2 – Drivers of biodiversity in forests

Our previous results showed that forest management is an important driver of biodiversity at the landscape scale. For example, in the Hainich-Dün region a subset of even-aged beech forests of different age classes (created by shelterwood cuttings) showed a higher gamma diversity than a subset of uneven-aged beech forests (resulting from selection cutting; Schall et al. (2018) J. Appl. Ecol. 55: 267-278). Beyond that, interviews with local stakeholders illustrated the tight relationship among forest management (e.g., tree species selection, management system, and management history), diversity of natural conditions and land tenure. Consequently, a heterogeneous landscape may have contributed to a small-scaled land tenure and consequently to a diversity of management systems.

In this work package, we will combine the factors natural conditions, land tenure and management and relate them to different components of organismic biodiversity (alpha, beta and gamma diversity) in order to identify the most important driver. We will do this in four steps:

2.1 Analysis of the relationship between natural heterogeneity of a landscape and organismic biodiversity

2.2. Analysis of the relationship between land tenure (e.g., ownership structure, size of enterprises) and organismic biodiversity

2.3 Analysis of the impact of former forest management (within the past 50 years) on current forest structures and on organismic biodiversity

2.4 Analysis of interactions among influencing factors and quantifying their relative importance for organismic biodiversity across different spatial scales (from the plot to the landscape scale)

WP 3 – Regular, bilateral knowledge transfer

For a continuous knowledge transfer, practice-relevant results of the BE should be provided to forestry and nature conservation practice on a regular basis. Together with the central coordination office (BEO) and the local management teams (LMT) of the three regions, we want to establish effective communication channels preferably used by practitioners.

Identified effective communication channels are:

3.1 Regular provisioning of scientific results with practical relevance using the Knowledge Transfer Webpage (under construction) of the BE homepage, supplemented by a digital newsletter and a network of regional multipliers from forestry, hunting and nature conservation

3.2 Contribution to local information events and excursions with practical relevance and initiation of workshops to discuss open questions concerning forest management and biodiversity

3.3 Initiation of future transdisciplinary projects based on current questions from practice and biodiversity research, as such projects are aimed to consider potential trade-offs between ecology, economy and society that practitioners have to deal with every day, early in the project planning phase

Starting our knowledge transfer project within the Biodiversity Exploratories (BE) in 2017, we wanted to initiate and establish a more intensive exchange between science and practice in the three exploratory regions and beyond. We first concentrated on four aspects:

- Re-analysis of BE data with practically relevant and region-specific questions to enable a transfer of the results to scales relevant for forest management in the three regions

- Evaluation and assessment of the previous transfer of BE results into forestry and nature conservation practice

- Identification of communication channels to improve the bilateral transfer between BE and practice

- Evaluation of current practically relevant questions and topics that should be integrated into future research projects

Points 2 to 4 were examined using a survey among stakeholders and scientists, follow-up interviews with stakeholders and joint workshops.

1. Re-analysis of BE data with a practitioners focus

Data analysis were conducted in close cooperation with the core project ‘Forest Structure’.

We looked at:

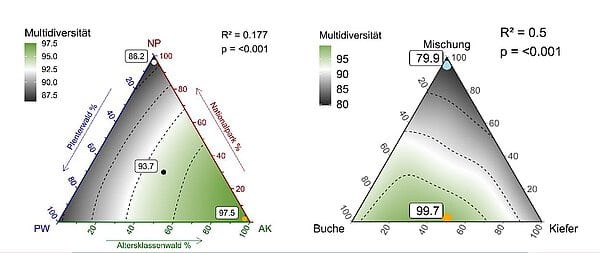

(1) The influence of different forest management systems of European beech (even-aged, uneven-aged, recently unmanaged) on regional (gamma)biodiversity in the Hainich-Dün

(2) The impact of mixed forests of beech and conifers (spruce and pine) compared to respective pure stands on regional biodiversity in the regions Schwäbische Alb and Schorfheide-Chorin

Our results underpin the importance of diverse forest landscapes for biodiversity as provided by different age classes of even-aged forests (Fig. 2, left) or pure stands of beech and different conifer species (Fig. 2, right). Even though recently unmanaged forests, as examined in the Hainich National Park, did not show a maximum biodiversity for most taxonomic groups, they were important for specific species groups like deadwood fungi or birds and should be an inherent part of forest landscapes

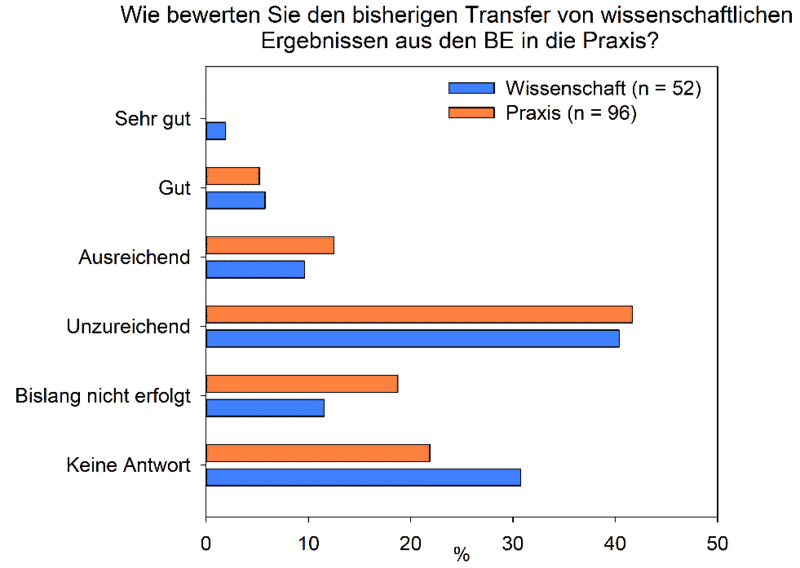

2. Evaluation of previous transfer of results into practice

To assess the previous transfer and to identify effective communication channels, we conducted a survey among different stakeholders of forestry and nature conservation in the regions and among scientists of the BE (Tab. 1). We concentrated on regional stakeholders with a direct influence on management decisions (e.g., representatives of different forest ownership categories, different administrative levels of public forestry and nature conservation, representatives of NGOs).

Tab. 1. Participation in the survey in spring 2018

| Practice | Science | |

| Number of questionnaires (n) | 736 | 174 |

| Ratio Forestry / Nature conservation | 85 / 15 | |

| Valid responses (n (%)) | 165 (22) | 52 (30) |

Only 58 % of the regional stakeholders knew the Biodiversity Exploratories. When known, the previous transfer of knowledge was predominantly rated as deficient (Fig. 3). Scientists provided similar answers.

Most stakeholders know the BE from their professional life. Other main sources of information were direct communication with scientists of the BE, local information events, printed information material, and the responsible forest office.

As main constraints for a successful transfer, stakeholders and scientists mentioned a missing communication between science and practice (52 % of practitioners, 72 % of scientists) and a deficient communication of results (54 % and 56 %). Also, specific framework conditions in practice (e.g., administrative issues) and science (e.g., restricted contracts) were mentioned as constraints.

59 stakeholders agreed to a follow-up interview; 36 people were already interviewed.

3. Effective communication channels to improve the bilateral transfer

The survey provided many suggestions for improving the bilateral transfer in the future. The interviews and joint workshops were used to specify these ideas.

We identified the following effective communication channels:

- Regional information events and excursions: important for a direct communication of research results; enables personal contacts, queries and discussions

- Homepage: to present practically relevant results of the BE in a short, comprehensible and regular way. Advantages over printed media are the topicality and availability at any time

- Electronic Newsletter: to point to new results provided at the homepage

- Personal communication via e-mail or during workshops. Such workshops, which aim to facilitate the integration of practical experiences and practically relevant questions into scientific research

- Publications in German in applied and practical journals

4. Evaluation of current practically relevant questions and topics

By conducting the survey among stakeholders and scientists, we also wanted to compile important and currently relevant questions of practitioners that should be included in future research projects. Questions were specified and evaluated during the follow-up interviews and workshops.

We compiled 49 research questions of three main topics:

I. Effects of forest management on biodiversity

a) Effect of different management regimes, including no management

b) Effect of old and habitat trees

II. Biodiversity and climate change

III. Socio-ecological assessment of biodiversity as well as questions regarding the control of success of established measures for biodiversity protection

The questions were distributed to the scientists of the BE and to prospective researchers of the BE to be included in future research projects.

- Dr. Jan Engel (Federal Competence Centre Forestry, Eberswalde)

- Dr. Martin Flade (Biosphere Reserve Schorfheide-Chorin)

- Dirk Fritzlar (Public Forestry Office (PFO) Hainich-Werratal)

- Manfred Großmann (Hainich National park)

- Dr. Volker Häring (Biosphere Reserve Schwäbische Alb)

- Matthias Kiess (PFO Reutlingen)

- Elger Kohlstedt (PFO Leinefelde)

- Achim Otto (PFO Heiligenstadt)

- Ingolf Profft (Forest Research and Competence Centre Gotha)

- Jörg Willner (Forestry and Landscape Management, City Mühlhausen)